Digital Philology

Reading an apparatus criticus is hard enough for a human to do; for a computer, it's impossible—at least if the apparatus hasn't been encoded.

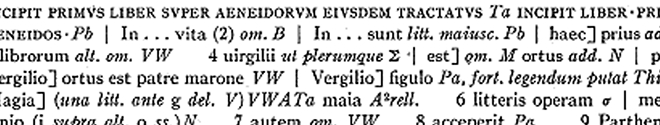

Critical editions in print are heavily encoded, but in a way that only humans with special training and lots of experience can decode. Because publishers prefer not to sacrifice much real estate on a page to printing information that they think only some readers will use, textual scholars have developed a way of compressing the information into the allotted space using abbreviations and symbols. Call it a “print-optimized visualization of textual data.”

The image in the header of this page is an excerpt from the so-called Harvard Servius. Consider all of the types of information that appear in the entries on a single page:

All of that information is communicated soley through visual, typographical means. And that’s not even the half of it, when you consider all of the information that readers have to bring with them to understand and interpret it.

Editors of print editions rely on readers to decode the various visual cues provided by symbols (e.g., manuscript sigla, punctuation, special characters, etc.), typographical conventions (e.g., italics , boldface , and roman type), and abbreviations. Without access to a clear legend at the beginning of a printed edition, a reader can become confused, especially since different publishers use typographical conventions differently. In a digital edition, however, editors can encode meaning directly. Instead of relying on a reader to understand that roman type denotes a variant reading and italic type indicates editorial remarks, the editor can use Extensible Markup Language (XML) to make those distinctions explicit, so that readers do not have to divine what is meant by a typographical convention.

In other words, digital editions give editors more control over communicating what they think is important and meaningful information. How that information is displayed depends on the needs of a particular reader or group of readers.

Content, not Display

In the world of print publication, the content of an edition is literally bound together with its presentation. That is, a lot of elements that aren’t meaningfully related to the contents—the cover, binding, the size of the page, the quality of the paper, the typography—have nothing to do with the content of the edition, but they’re nevertheless part of it. That has an effect on the usability of the edition as a whole, since the size of the page limits the amount of information it can hold.

With a digital edition, it’s important to separate format and presentation from content, since the information in a digital edition can be presented in a variety of ways. We can design a layout that resembles a traditional printed edition, which is useful if someone wants to have a hard copy. But we can also offer online users the ability to change the amount of information available to them at any given time. Perhaps you don’t want to see any variants, or only variants from a certain manuscripts family, or only conjectures by modern scholars—all of that is possible with a digital critical edition. Or maybe you want to see the text with variants from a certain manuscript in place. Then there’s the chance that someone might want to toggle on and off various morphological, lexical, and visualization tools. Someone might want to have access to images of manuscripts and diplomatic transcriptions of them. Whatever the case may be, all of these things have to do with the presentation of a digital edition, not its content.

At least as far as the LDLT is concerned, we use the word “edition” to refer only to the information, or data, provided by editors, regardless of the format that it might take when users work with it. Our goal is to provide authoritative, reliable, critical editions that are valuable in and of themselves as works of scholarship, but that can also be presented in a variety of formats for a variety of uses—from hard copies bound by a print-on-demand service to an eBook format for use on computers and mobile devices to tokenized data for use in sophisticated information visualization applications.

This notion of “one format, many uses” is at the heart of XML, which is the encoding language behind many popular word processing programs that allow you to save your work in multiple formats, including pdf, html, and plain text, among others. The same is true for LDLT editions. Instead of being constrained by any one format, we can use XML to separate information from its visual presentation, all the while making the information easier to understand. How that information is presented will depend in large part on the way the user wants to interact with it.

DLL Displays

Of course, LDLT editions wouldn't be user-friendly if we didn't provide some way of viewing them, so the DLL offers four ways of interacting with LDLT texts.

- Since most users just want to see the text and any editorial annotations associated with it, the LDLT reading room provides a clean view of the text with links to annotations about variant readings or other information the editor has deemed important.

- For users wishing to view an edition in a more traditional format, we provide a PDF version with all of the trappings of printed critical editions. This is one of the DLL's ongoing research projects. It involves customizing the TEI's XSLT Stylesheets to transform an edition's XML into LaTeX. You can see an example of this project at https://github.com/Library-of-Digital-Latin-Texts/balex/raw/main/ldlt-balex.pdf.

- For users who want to delve into the data, the LDLT also has a downloadable desktop application (warning: linked file is 44MB) with sophisticated tools for visual data analysis. Chris Weaver and his assistants have developed a number of sophisticated text visualization tools that will help users see critical editions in new ways—from pixel-based visualization of variants to storyboard visualizations of witness groupings. Users who want to view the data in some other way can download the raw XML files and work with them independently of the LDLT’s applications.

- The XML for every edition, along with any other data an editor might wish to include (e.g., collation tables, images, transcriptions, etc.) is available in a publicly accessible Git repository on GitHub. Indeed, the repository is what the DLL publishes. All of the visualizations are just that: visualizations of the published data.

The important thing to remember is that the presentation of that data is separate from the data itself. In other words, what matters is the scholarship that goes into making the edition authoritative and reliable, not the way it looks after it goes to a professional typesetter and publisher. That’s why we’re interested only in providing a clean version of the edition in the LDLT reading room. If someone else has a novel way of presenting the data, we’re happy for the data to be reused for that purpose, but it is not the mission of the LDLT to provide every presentation possible.

Markup as Scholarship

All of this means that semantic markup with XML must be considered part of the original, scholarly contribution of a digital critical edition, which in turn means that there must be a way of evaluating markup as scholarship. Accordingly, the DLL project is developing a rubric for assessing the quality of scholarly markup in editions submitted for publication in the Library of Digital Latin Texts. This rubric takes several standards into consideration, including not only adherence to the long-standing best practices of textual criticism, but also the guidelines established by the Text Encoding Initiative for using XML in scholarly editions.